J. Robert Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb, is the subject of Christopher Nolan’s latest movie “Oppenheimer” nearly 80 years after his life’s work made history and changed the world’s trajectory.

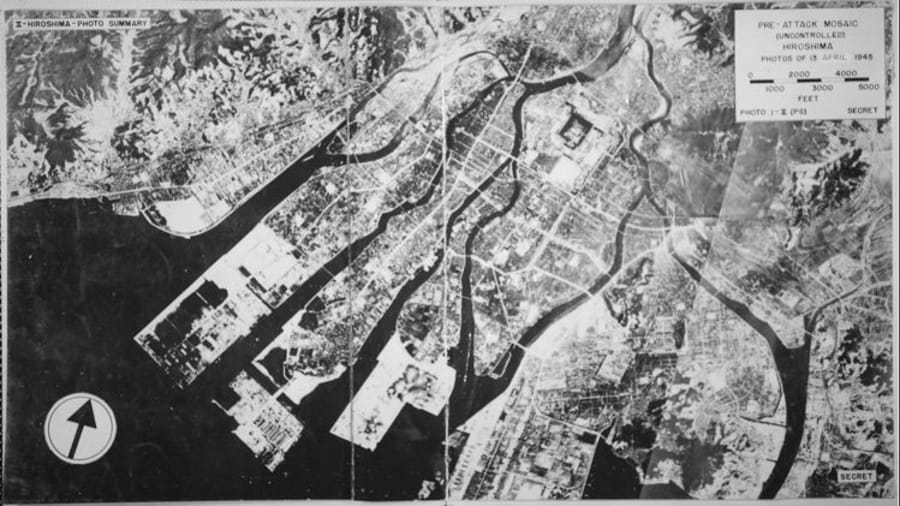

As the head of the Manhattan Project, Oppenheimer’s bombs killed between 110,000 and 210,000 people during World War II, obliterating the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. The bombs are commonly cited as the main factor in Japan’s surrender, which ended the war.

Many Americans consider Oppenheimer a hero. Though there have been some shifting opinions on the bombings in the decades since, the physicist remains well known and relevant today.

Oppenheimer’s start before WWII

Oppenheimer enrolled at Harvard in 1922, where he studied chemistry before deciding to become a theoretical physicist. After graduating in 1925, Oppenheimer studied overseas in countries like Germany and England, where he collaborated with British scientists to advance atomic research.

He returned to the U.S. to teach physics at the University of California in Berkley and the California Institute of Technology after visiting science centers abroad.

California was where Oppenheimer began dating Ann Arbor-born Jean Tatlock in 1936. She was a member of the American Communist Party who, Oppenheimer said, played a roll in introducing him to left-wing friends. While Oppenheimer never officially joined the party, and said he never accepted the Communist theory, his alleged Communist sympathies, friendship with communist party members, and marriage to then-party member Kitty Puening contributed to one of the most controversial moments in Oppenheimer’s life.

WWII and the Manhattan Project

Oppenheimer and other physicists’ theoretical work became practical when the Manhattan Project was created in August 1942, during World War II.

The United States learned that Nazi Germany had a nuclear program, and scrambled to create an atomic bomb, believing whoever created it first would win the war. Oppenheimer became the project’s leader, and chose Los Alamos, New Mexico as the location where a majority of the atomic bomb research would be conducted.

Los Alamos was a secret town built for the project that spanned 46,000 acres. It was not on any map, employees could not tell anyone where they worked, and babies born there had “P.O. Box 1663″ listed as their birthplace on birth certificates.

Oppenheimer spent the first three months of 1943 searching the country for scientists to recruit to Los Alamos. Recruits began arriving with their families in March, turning Los Alamos into a boomtown overnight.

That June, Oppenheimer told Los Alamos security he was going to visit Berkley to recruit an assistant. In reality, the main reason for the trip was to see former girlfriend Jean Tatlock, who was on the FBI’s suspect list because of her Communist party membership, according to historians.

The two had dinner before spending the night at Tatlock’s apartment. Meanwhile, FBI agents followed Oppenheimer the entire trip, tapped Tatlock’s phones, and spent the night in a car across from her apartment to monitor the two.

As promised, Oppenheimer hired an assistant during the trip named David Hawkins -- but Hawkins’ own Communist sympathies put Oppenheimer in an even worse light.

Work continued for two years until two bombs were created: “Little Boy” and “Fat Man.” The latter needed testing, which was conducted 210 miles from Los Alamos on July 16, 1945, with leadership watching 20 miles away.

As the bomb was being raised into its tower for the test, workers froze when it became unhinged and began to sway. Observers panicked at the possibility of the bomb accidently falling and detonating.

Concern was fueled further by previously failed tests, a city of 70,000 people just 300 miles away, and project member Arthur Compton’s fear that the blast would ignite the atmosphere and vaporize the planet. Any mistake could mean disaster.

Instead, the bomb was steadied and raised to the top of the tower. It detonated at 5:29 a.m.

The explosion was immense. A mushroom cloud rose 38,000 feet. The explosion created a crater a half-mile wide; its heat turned sand to glass; a light “brighter than a thousand suns” was seen states away.

“I guess it worked,” Oppenheimer told observers.

Celebration gave way to horror as a chill settled among the scientists in the desert. Oppenheimer famously said the Trinity test reminded him of a line from the Hindu holy text, the Bhagavad-Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

How would weapons that could destroy the planet be used in the future? The question would haunt Manhattan Project scientists for the rest of their lives.

Three weeks later, the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The war with Japan was over.

After WWII, Oppenheimer accused of spying

The start of the Cold War with the Soviet Union in 1947 brought fears of Communists in the U.S.

The Cold War and rivalry with the Soviet Union raised fears in the U.S. that American Communists and left-wing citizens would work as Soviet spies and threaten U.S. security. President Truman issued a “Loyalty Order,” which called for all federal employees to be analyzed to decide if they were loyal to the United States.

Oppenheimer’s past was made public in December 1953, when he was accused of associating with Communists and not disclosing names of Soviet agents. His past, along with his opposition to the hydrogen bomb, which was developed in response to Soviet nuclear tests, caused the Atomic Energy Commission to question if Oppenheimer was actually a Soviet spy.

A hearing was held and Oppenheimer was afraid of accidently spilling classified information, causing him to censor his own defense. A lack of security clearance also meant the defense did not have access to important evidence that could have helped Oppenheimer’s case.

To the outrage of the scientific community and many American citizens, Oppenheimer became a victim of the Red Scare and had his security clearance revoked. In a different hearing, just one vote kept Oppenheimer from going to prison.

Oppenheimer today

Since Oppenheimer’s death in 1967, he and the Manhattan Project have appeared in many forms of pop culture including movies and TV shows like “Manhattan” and novels like “The Wives of Los Alamos.”

Public opinion of the bombings has also changed. In 1995, half of respondents said they would have tried to force Japan to surrender another way. In 2015, 56% of Americans said the bombings were justified, compared to the 85% of Americans that approved of the bombings in 1945.

In 2016, Barack Obama became the first sitting president to visit Hiroshima, where he called for a world without nuclear weapons.

Then in December 2022, the U.S. reversed the 1954 decision to revoke Oppenheimer’s security clearance, saying the decision was made using a “flawed process” that actually violated the Atomic Energy Commission’s own regulations.

The largest black mark on Oppenheimer’s career was wiped away.

Christopher Nolan’s film depicting Oppenheimer’s role in the Manhattan Project is slated to premiere on Friday, July 21.