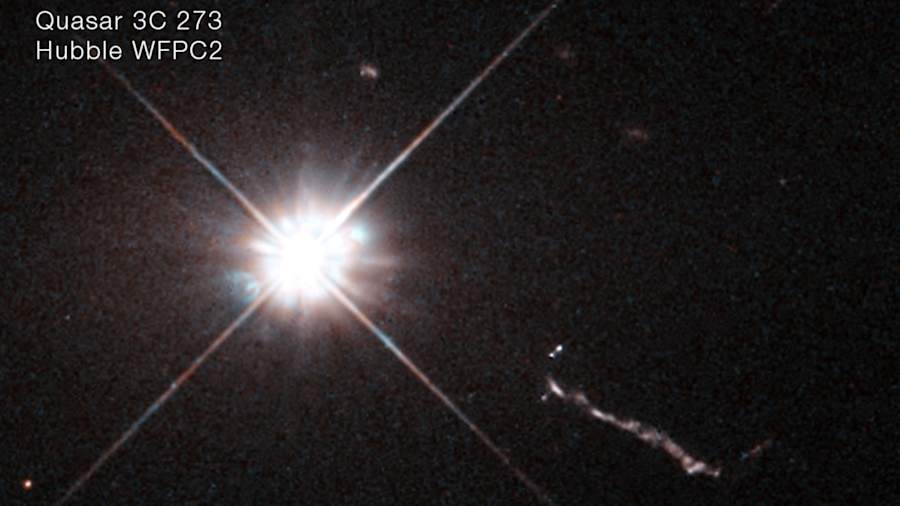

This is a picture of the core of a quasar.

Specifically, it’s a Hubble Space Telescope image of the core of quasar 3C 273. It’s 2.5 billion light-years away from Earth. It was discovered in 1963 and it is the first quasar (quasi-stellar object) ever discovered.

If you’re like me, you’re probably thinking, “Cool! But what is a quasar?” To understand what a quasar is, NASA wants you to picture a region the size of a solar system that pours out 100 to 1,000 times as much light as a galaxy containing a hundred billion stars. It creates a glow that outshines its host galaxy and everything in it.

Quasars are distant galaxies whose bright cores are powered by supermassive black holes. According to NASA, quasars occur “when immense amounts of matter fall into a supermassive black hole, spiraling around it in the form of a disk before entering.” The disk is under extreme gravitational and frictional forces, which causes the gas and dust to heat up, become luminous, and blast material out into the university.

To the untrained eye, this might look like just a cool photo, but to Bin Ren of the Côte d’Azur Observatory and Université Côte d’Azur in France, it shows a lot of “weird things.”

“We’ve got a few blobs of different sizes, and a mysterious L-shaped filamentary structure. This is all within 16,000 light-years of the black hole,” Ren said. NASA said some of the objects could be small satellite galaxies falling into the black hole.

In 1994, Hubble captured an image that revealed the environment surrounding quasars is more complex than first suspected. The images indicate collisions and mergers between quasars and companion galaxies, where debris cascades down onto supermassive black holes. That reignites the giant black holes that drive quasars.

When Hubble looks into quasar 3C 273, NASA said it’s “like looking directly into a blinding car headlight and trying to see an ant crawling on the rim around it.” In simple terms, the quasar is very, very bright.

Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) can work as a coronograph, and is used to block light from central sources. Astronomers have used STIS to reveal dusty disks around stars to understand how planetary systems are formed. They’re also using STIS to understand quasars’ host galaxies.

The Hubble coronograph helped astronomers look eight times closer to the black hole than ever before. This gave scientists “insight into the quasar’s 300,000-light-year-long extragalactic jet of material blazing across space at nearly the speed of light.”

“With the fine spatial structures and jet motion, Hubble bridged a gap between the small-scale radio interferometry and large-scale optical imaging observations, and thus we can take an observational step towards a more complete understanding of quasar host morphology. Our previous view was very limited, but Hubble is allowing us to understand the complicated quasar morphology and galactic interactions in detail. In the future, looking further at 3C 273 in infrared light with the James Webb Space Telescope might give us more clues,” said Ren.

NASA said at least 1 million quasars are scattered across the sky. They were most abundant about 3 billion years after the big bang, which is when galaxy collisions were more common, according to NASA.

Want to read more about black holes? There’s an article from NASA called “Monster black holes are everywhere” -- click here to read it.